Louise Wingrove is a doctoral student in her final year based in the Drama: Theatre, film and television department at the University of Bristol. Her research is concerned with investigating the career development, self promotion, success and material of the Victorian music hall serio-comedienne through her case studies of Jenny Hill (1848 – 1896) and Bessie Bellwood (1856-1896). Her wider interests include performance history, the development and history of women in comedy and use of comic performance in the Suffrage movement.

Deciding what to write about in this post proved more complex than I had initially anticipated. Sharing my research and passion for Victorian music hall serio-comediennes excited me as I imagined all the angles that I could take. Yet none of them presented my case studies quite right and it was with this in mind that I was drawn back to thinking about my methodological approach to performance histories.

My concern when researching Victorian female comics is how best to reimagine and rediscover their careers, lives and material in order to see them as three dimensional performers, not two dimensional images on paper that are distorted by the lens through which they are viewed. I quickly realised that the essential ingredient to my research was a multidisciplinary methodology. I read thousands of reviews, found interviews and photographs and conducted wide spread social research for the late nineteenth century. I analysed sheet music and trawled through endless licensing and safety reports from Victorian music halls. Certainly, I can talk about these methods individually, but the fulfilment of my aims to reimagine and rediscover these women relies on the ways they weave together to produce a fuller image of the performers I am researching. I therefore wish to share the evolution of my methodology in order to invite discussion and input as to the importance and exciting new information we as researchers glean from a multidisciplinary approach as well as to show how it works in the world of performance histories.

When tracing the history of the female stand up comic I discovered that were a remarkably large amount of popular female comics on the Victorian music hall stage. For those unfamiliar with serio-comics, they were performers whose acts alternated between comic and serious songs and sketches, interspersed with patter and audience interaction. They relied heavily on satirical songs and their material can be seen as an embryonic form of the stand-up comedy we enjoy today. These serio-comics would perform their material on the music hall stage as part of a variety bill during which acts such as performing animals, dancers, acrobats and scenes from ballets and operas would be performed to a largely working class audience. Music hall was seen by many as ‘illegitimate’ theatre compared to it’s ‘legitimate’ counterpart offering full length, conventional plays and theatre censorship at the time prevented music halls from producing a full length play with linear storyline as this was something only permitted in fully licensed ‘legitimate’ venues. It is well documented that, in Victorian society, it was often considered unwomanly to be seen speaking in public. Therefore, with music halls signalling something sordid compared to mainstream, legitimate theatre, the question could be raised as to why a woman would desire a career in the music hall?

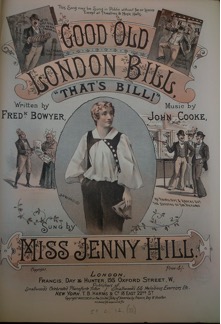

Jenny Hill. Image courtesy of http://www.themusichallguild.com, who I highly recommend for any information about music hall stars

In a letter from a leading actress in 1892 it was claimed “In a music hall, a woman certainly has a chance of living on her salary and has to depend on her talents.[1]” The letter went on to explain how, as an actress, the salary was usually around £2 a week for everything – to live off and to pay for their own costume. At the height of her career, popular serio-comic Jenny Hill (1848-1896) could earn as much as £80 for twelve days work and was also given a benefit night by the hall managers, during which she would usually receive expensive gifts and jewellery.

In the same year performer Fanny Leslie was asked why she only performed in the halls. She answered, “I like to make my own successes, and I work hard to earn them, and I don’t like to be robbed of the fruits of my labour by other people’s incompetence. On the halls I choose my own songs, arrange my own business, and if I fail to make a hit it is a satisfaction to know that no one is to blame but myself.”[2] But were these women the exception to the rule? Though not taking into account their popularity and material, in 1892 the Theatre and Music hall Journal announced that during “…the great popularity of sketches in the week before Christmas, out of 341 turns appearing in the 25 sketches; of lady serio-comics there were 76; male comedians, 74…”[3] indicating that these women were not as rare as we often expect.

Indeed, programs and advertising from this period provide evidence of a wealth of celebrated female comics. Through tracing adverts, reviews and interviews in industry newspapers such as The Era, I could trace their touring schedules and what material was popular and where. However, with newspapers being a biased resource, these performers need a more multidisciplinary investigation to give them back the independence and career pride they valued so highly whilst also celebrating our comedy history. I therefore needed to pick two performers to investigate, namely Jenny Hill and Bessie Bellwood (1856-1896). These women were highly popular with audiences, earned enormous sums of money and, in the case of Jenny Hill even showed aspirations and attempts to move into theatre management. Simultaneously, reviews patronisingly describe Hill as a ‘clever little lady’ and implied that she was a kept woman with her huge farm in Streatham being bought for her rather than her herself buying it from her own earnings[4]. The way both women were described as simply performing ‘low comedy’ seems to grate against biographical information and interviews connected with the women and their methods of picking songs and characters. More biographical information is needed to place the newspaper information into context, but without the newspaper information tracing characters and tours is near impossible. The two must work together.

None of this information works without the additional use of sheet music to understand their material. Yet, in the same way that their careers have been largely forgotten, sheet music for both performers is sparse. Bessie Bellwood currently only appears to have three pieces of sheet music to her name, Jenny Hill fares slightly better with twenty-two. In isolation, these pieces of sheet music shed a peculiar light on these women’s repertoires and, rather than answering questions regarding their popularity, pose more questions as to why they were  popular – especially with women. Conventional drinking, romantic and patriotic songs make up the bulk of those on offer, with Hill occasionally displaying something slightly different in the highly political nature of her songs. This music generally makes Hill and Bellwood conform to our ideas of ‘typical’ music hall material and singers. Nevertheless, if you add details of reviews and trace what was being sung in what hall, one discovers that many of the songs published are actually rarely discussed in reviews. Instead, songs that are noted as being popular are songs about coffee shop girls, barmaids, costermonger and songs that convey the everyday lives most likely enjoyed by the audience. However these song topics would have been unlikely to be enjoyed by or bought by the middle and upper classes known for buying sheet music, so are less likely to have been published, and this in turn skews our understanding of these performers and their acts. Sheet music analysis remains an integral part of music hall study and is a technique I am still using extensively in my thesis. Being able to sing and record the songs available gives an insight into a performers range. The lyrics give an essence of social context and the ambiguity employed in song writing at this time. Similarly, by using reviews one can see what costumes they may have worn to perform the songs and any patter included, adding life to the sheet music. This method looses its potency when it is taken out of context and investigated without the newspaper and biographical information to make sense of it. Case studies of the music halls where the songs were performed also helps make sense of repertoires and how the printed songs fitted within them as one can build a picture of the types of audience frequenting these halls by looking at programme and drinks prices, the images on bills and the types of products advertised.

popular – especially with women. Conventional drinking, romantic and patriotic songs make up the bulk of those on offer, with Hill occasionally displaying something slightly different in the highly political nature of her songs. This music generally makes Hill and Bellwood conform to our ideas of ‘typical’ music hall material and singers. Nevertheless, if you add details of reviews and trace what was being sung in what hall, one discovers that many of the songs published are actually rarely discussed in reviews. Instead, songs that are noted as being popular are songs about coffee shop girls, barmaids, costermonger and songs that convey the everyday lives most likely enjoyed by the audience. However these song topics would have been unlikely to be enjoyed by or bought by the middle and upper classes known for buying sheet music, so are less likely to have been published, and this in turn skews our understanding of these performers and their acts. Sheet music analysis remains an integral part of music hall study and is a technique I am still using extensively in my thesis. Being able to sing and record the songs available gives an insight into a performers range. The lyrics give an essence of social context and the ambiguity employed in song writing at this time. Similarly, by using reviews one can see what costumes they may have worn to perform the songs and any patter included, adding life to the sheet music. This method looses its potency when it is taken out of context and investigated without the newspaper and biographical information to make sense of it. Case studies of the music halls where the songs were performed also helps make sense of repertoires and how the printed songs fitted within them as one can build a picture of the types of audience frequenting these halls by looking at programme and drinks prices, the images on bills and the types of products advertised.

Within all of these methods, an enormous amount of information is accrued and packaging it into something neat and easy to discuss proves tricky yet worthwhile. There are also some pieces of archival information that are wonderful, yet don’t fit into any set contexts, and so I will end with my favourite odd find.

Image courtesy of http://www.buttonmuseum.org

This badge of Bessie Bellwood was produced in 1896 in Newark, America, as advertising for Sweet Caporal cigarettes. It is now part of the Busy Beaver Button Museum collection in Chicago. It immediately intrigued me due to what it tells me about Bellwood’s American tour. She went to America twice in the 1890’s and proved popular, producing and singing a song called Uncle Sam especially for her American audience and also buying the performing rights to the song Trilby from Marie Lloyd. However the fact that her image was used on a badge for advertising indicates how famous she must have become, this surviving badge offering an insight into the small amount of time she spent out there. It is one of those strange items that makes me smile and reminds me of how these little things can be connected and pinned together to form something fascinating.

[1] Theatre and Music hall journal (June 4th 1892)

[2] Theatre and Music hall journal (9th September 1892)

[3] Theatre and Music hall journal (May 28th 1892)

[4] Bratton, J.S.. “Jenny Hill” in Music hall. Performance and style. Ed. J.S Bratton. Milton Keynes: Open University Press, 1896. P96

A friend of mine is trying to find information on Lizzie Evans, who was said to give Lotta Crabtree competition. Have you run into sources that might help? Thanks

Pingback: Nunhead Cemetery | The Endless British Pub Crawl continues...·