Sarah Kuenzler is an independent researcher who holds a Masters in Art History from the University of St. Thomas in St. Paul, Minnesota. Her thesis focused on the orientalization of the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyam by the American artist Elihu Vedder, and her current research delves into aspects of racism and the collectable minority of 19th century trade cards. You can follow her on Twitter @19thAmerican.

The popularity of the American trade card grew at just the right social and cultural climate in nineteenth-century America. Because of advances in color lithography processes, the spread of people and transportation out West, and a growing number of businesses in need of quick marketing tools, the trade card became the cheap and easy go-to for American entrepreneurs to easily market their goods to a wider number of the increasingly literate populace. Soon, the trade card came to be more than an advertisement; it became a form of entertainment in the American home. Some included jokes, riddles, or even physical puzzles for the consumer to solve. In the course of American Enterprise history, no other form of advertising had a more significant and engaging effect in popular culture than the Trade Card.

Before the introduction of lithography to the United States, Trade Cards existed mainly in engraved form. These black and white cards, produced by copperplate engraving,[1] were influenced largely by British imagery in the early nineteenth century. In the time before the American Civil War of the 1860s, the most complex and impressive imagery on Trade Cards was produced in Philadelphia, where many engravers were direct emigrants from Britain.[2] Color lithography was introduced to the Americas in the 1830s, and is credited to the young French immigrant Peter S. Duval. Duval had experience with lithography in his native France, and so brought that knowledge to Philadelphia, where both trade cards and advertising in general were

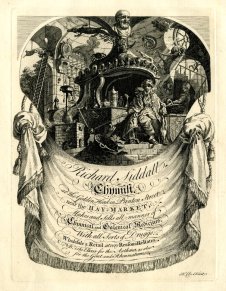

growing into booming businesses. From the cheaper and easier lithography process rose the notable printing companies of Louis Prang, Currier and Ives, and the Bufford Company of Boston.[3] A trade card advertising a lithography service can be seen in figure 1 . Printed between 1830 and 1840, this card shows the British influence in its imagery and approach to advertising. When compared to figure 2 , a British trade card printed at the end of the eighteenth century by Richard Siddell in London, the similarities between use of space and text are obvious. The cluttered foreground displaying as many items or people as possible and the format of the card itself with the image on top and the text on the bottom are an example of the visual influence British advertising design had on American trade cards at this time.

By the mid-1800s, the imagery had taken on a decidedly American tone – particularly in the use of minority groups, such as African and Native Americans. Not surprisingly, these two peoples were in flux within American society at that time – Native Americans had been and were in the process of displacement to reservations, while African Americans were largely enslaved in the southern United States. The divisive North versus South sentiment was growing, and recent western expansion was threatening to add a State to the side of the North, leaving the South lacking in territories where slavery was allowed.

Trade cards produced in the mid- to late-nineteenth century show the changing attitudes towards minority groups. As a result of the end of the Civil War and the abolishment of slavery, a great many African Americans fled the South for the promise of success in the North in what became known as the Great Exodus of 1879. Between the 1860s and 70s, African American imagery became more and more comedic, as seen in figures 3 and 4. This imagery reflected the largely anti-black sentiments shared by both Southerners and Northerners, as the illiterate and uneducated African American population made their way into the Northern states. In figure 3 , a

trade card advertising Beeman’s Improved Grain Separator, an African American morphed into a literal anthropomorphic watermelon is an appalling example of how low in society African Americans stood, even a decade after the Civil War. Figure 4 shows an interior scene, where the two older women represent the comical characters “Aunty Fat” and “Auntie Lean.” While the imagery type seen in this example – the bulbous lips, the lazy caricature, and the implications of low ambitions – is seen in imagery depicting both caucasian and minority figures, the amount by which African Americans are depicted in this manner far outweighs the amount for other cultural groups.

(Figure 5)

Trade Cards, however, did not always depict figures; sometimes the cards themselves were used for their entertainment qualities. The trade card in figure 5 is not a card at all, but is a small envelope containing a puzzle. Each puzzle piece advertises the “Kenwood Phonograph,” which the consumer would learn about by putting the puzzle together. A genius way of advertising, cards like these made the consumer implicit in their own consumerism. Another example of this “active trade card” can be seen in figure 6 , an easel-shaped card advertising for Golden Eagle Clothing House. Printed at the very end of the ninetenth century, this card shed the previous rectangle shape other trade cards

adhered to in favor of the shape of an artist’s easel. The consumer could hold the card by inserting a figure through the hole at the top, thus holding the card as an artist would hold an easel

By the beginning of the twentieth century, trade cards as a way of advertising had fallen out of favor. In exchange, newspaper and magazine advertisements, as well as postcards, became popular means of communicating product value to the American public. Trade cards represent the very beginning of the American consumer advertising empire; a way to convince the population to not only buy the item the card extolled, but to value the card itself. Trade cards integrated advertising into the American private household in a way that twentieth century methods could never replicate.

[1] Jay, The Trade Card, 7.

[2] Ibid., 9.

[3] Ibid., 24.

figure one

figure 2

figure 3 – Beeman’s Improved Grain Separator

figure 4

figure 5

figure 6

Hello

You may interested in the following http://tinyurl.com/j9mobbd. You can also see images if you drill down through the pages

The attractive artist’s palette shaped card is a great example both of the impact made by chromolithography on American trade cards and of the ability to die-cut the cards to shape them—both these processes were also used to produce advertising bookmarks. One trade card cut in the shape of a fan was issued by a Turkish bath in Kentucky (http://tinyurl.com/zw7ebo3).

Both these cards illustrate also that neither image nor shape had any connection with what was being advertised. While there were exceptions which were more costly for the advertiser, most were standard cards selected from a printer’s sample book and overprinted either on the image itself, or in an area left blank within the image. Often, as was common with Turkish baths cards, the reverse was used to indicate opening hours and other relevant information.

Like your collectable phonograph cards, and the ubiquitous cigarette card, series of cards were especially popular with services such as Turkish baths to encourage bathers to return and add a new card to their collection.

The attractive artist’s palette-shaped card is a great example both of the impact made by chromolithography on American trade cards and of the ability to die-cut the cards to shape them—both these processes were also used to produce advertising bookmarks.

One trade card cut in the shape of a fan was issued by a Turkish bath in Kentucky (http://tinyurl.com/zw7ebo3).

Both these cards illustrate also that neither image nor shape had any connection with what was being advertised. While there were exceptions which were more costly for the advertiser, most were standard cards selected from a printer’s sample book and overprinted either on the image itself, or in an area left blank within the image. Often, as was common with Turkish baths cards, the reverse was used to indicate opening hours and other relevant information.

Like your collectable phonograph cards, and the ubiquitous cigarette card, series of cards were especially popular with services such as Turkish baths to encourage bathers to return and add a new card to their collection.