Emily Turner is a first year doctoral candidate at the University of Sussex, where she is studying the medical humanities with a specific focus on locating archives of patient publications produced in mental health institutions between 1850 and 1950. You can find out more by following her at https://twitter.com/emilyjessturner, or read more of her journalism and academic writing at https://emilyjessicaturner.wordpress.com.

In in late September of this year, I was lucky enough to hear Sarah Perry reflect on her second novel, The Essex Serpent, at an evening event held at Royal Holloway. With wit and humour, Perry discussed her process of researching for her latest work, which was published earlier this year – a process, she made clear, that she would not recommend to anyone. “Please don’t ever emulate my research practice,” Perry told the audience, made up partly of Victorianists and creative writing students. “I just tend to write, and then check the history on Google afterwards to correct my own misinformation – it’s a form of confirmation bias.”

“So, for example, I wanted to write about nineteenth century heart surgery, so I went and found out about the pioneering work they did in Edinburgh during this period. I’m like three years early but I couldn’t care less – it’s all about the idea.”

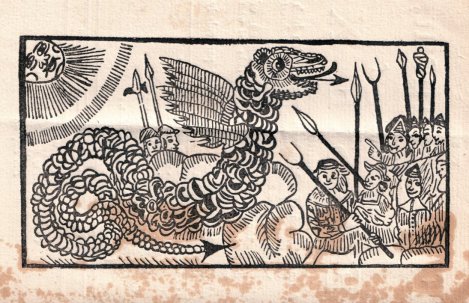

Image: A woodcut from a 1669 pamphlet called ‘The Flying Serpent or Strange News Out of Essex’, reproduced in The Essex Serpent by Sarah Perry review – a compulsive novel of ideas, by M John Harrison

The creature, supposedly a ‘monstrous serpent with wings like umbrellas clacking its beak on the common’(14), resurfaces in Perry’s own neck of the woods, Essex, in a village known as Aldwinter. Moving between this rural space and London, this is a novel which is set within a deliberately ambiguous timeframe. Although dated 1893, the author has consciously written a novel which could be set either in the latter nineteenth century or today.

Time is a malleable force within this novel, changing depending on individual context. The Essex Serpent opens: ‘One o’clock on a dreary day and the time ball dropped at the Greenwich Observatory […] Time was being served behind the walls of Newgate jail and wasted by philosophers in cafes on the Strand; it was lost by those who wished the past were present, and loathed by those who wished the present past. Oranges and lemons rang the chimes of St Clement’s, and Westminster’s division bell was dumb’ (11).

Reflecting this playful interpretation of time, Perry’s book operates as a site in which both Victorian and neo-Victorian historical influences compete.

As a historical novel, informed by historical research and peppered with references to the ‘real’ history researched by Perry herself, the author has selected to explore various ideas within her work that reflect contemporary concerns and ideologies. The housing and rent issues experienced in the UK today are echoed by Perry’s socialist companion Martha, who feels fiercely about the expensive, cramped and unsanitary housing provided in London in the 1890s. Today’s race to fight diseases such as cancer and create groundbreaking new treatments is represented by Dr Luke Garrett, the pioneering surgeon. “Hilary Mantel is God,” said Perry at her recent talk. “As she says, ‘all fiction is historical fiction’”. Regardless of setting, therefore, fiction speaks of the struggles we all face, and to our shared human experience.

As a neo-Victorian text, there are a number of intrusions of the contemporary into the Victorian. References to the impossibility of heart surgery and the unnamed autism of the protagonist’s son indicate to the modern reader a distance between the text’s era and ours.

However, it is worth considering that The Essex Serpent also represents the Victorian intruding into the contemporary, reminding us not only of the social changes we are still in the process of instigating and the discourses we are continually engaging in, but it also reminds us of the oft-forgotten modernity of the nineteenth century. Perry herself feels that the Victorian period must be recognised as a kindred spirit of our own. At her Royal Holloway talk, she said: “I was blown away by Matthew Sweet’s book Inventing the Victorians, which looked at the Victorian period as a truly modern era, discussing, among other topics, the Elephant Man, who was a very canny businessman.

“I thought to myself: ‘I’m going to write a “modern” Victorian novel’ – I almost wanted to trick people by doing something different, and writing a book that could exist in either time.

“To do this, I thought a lot about the language, using words such as ‘cab’ rather than ‘carriage’.”

Image: Sarah Perry, photographed by Jamie Drew, reproduced in The Essex Serpent by Sarah Perry review – a compulsive novel of ideas, by M John Harrison

There is no mistaking the intertextuality of the text, which clearly echoes Hardy and Dickens. “I can’t help but write the way I do,” said Perry. “It echoes all my influences. Jane Eyre is in my blood – cut me and you’ll see Thornfield written all over.

“I grew up in a fundamentalist sect, and the type of media I had access to was Victorian. I adore Hardy and Dickens and the Pre-Raphaelites – although I think some of my family members weren’t too happy to see so many nude paintings on my walls.”

Despite the obvious intrusion of the Victorian novel form and the Gothic into The Essex Serpent, the novel, as a neo-Victorian text, also has clear links to modern storytelling. On discussing the opening scene of her novel, in which a drunken man disappears into the dark waters of the Blackwater Estuary as the year ends on New Year’s Eve, Perry said: “Jaws is one of my favourite films ever. It’s dishonest to deliberately evade your influences.”

Despite these textual reminders of the modernity of the era, the Victorian setting, however, is ultimately crucial when considering the serpent itself.

Perry’s novel evokes a period in which palaeontology is in mode, as women wear jewellery formed from fossilised teeth set in silver and collect ammonites, and papers are regularly published hypothesising the ways and places in which ‘extinct’ animals may be found as living species.

Caught in the liberating and accessible new world of amateur natural history, Cora Seabourne, a devotee of Mary Anning and her ‘sea-dragons’, leaves London for Essex. Hearing tell of the Essex Serpent, a mythical beast which has apparently unleashed itself on the county after an earthquake and terrorises the local people, Cora is inspired to find a new species to document – to her, ‘all the earth was a graveyard with gods and monsters under their feet, waiting for weather or a hammer and brush to bring them up to a new kind of life’(189). As staunch in her atheism as she is in her very real hopes to find this mysterious undocumented creature, Cora soon meets Will Ransome, the rector of Aldwinter, whose faith in God and man leaves space for little in between – ‘there is more besides the counting of atoms, the calculating of the planet’s orbit, counting down the years until Halley’s Comet makes its return’(259), he says to Cora.

Positioned between the old world of magic, folklore and faith, and the emerging sphere of science, taxonomy and reason, and following the quest of a woman who hopes to find a creature who encapsulates both sides of the spectrum, The Essex Serpent seems to me a liminal space in which spheres intrude upon and within each other. Transitional worlds collide both within the author’s process of creating her book, as we have seen, and within the novel’s very narrative.

The author’s recreation of the mythical creature, who is supplanted from a seventeenth century pamphlet into a neo-Victorian novel, exemplifies this collision of perspectives. The Essex Serpent would be, as Perry has pointed out, interpreted rather differently in 1890 than in 1669.

In the early nineteenth century, texts on the relationship between religious faith and the sciences placed the two in ‘beautiful accordance’[2]. The study of ‘God’s Word, in the Bible, and His Works, in nature, were assumed to be twin facets of the same truth’[3].

A change can be seen in this mentality in the latter half of the nineteenth century, as scientific discoveries related to the natural world were encouraging a re-evaluation of worldview.

In addition to Darwin’s works on evolution and natural selection, ‘British men of science, particularly geologists, were also making discoveries which threatened the literal meaning of Genesis’[4], and the Victorian compulsion to archive and taxonomize led to a thorough documentation of the natural world. As Dawkins says, ‘evolution was in the air in the mid nineteenth century – a thrillingly radical notion which offered a way to make sense of a huge array of facts’[5]. The appeal of natural science was widespread – ‘amateur naturalism’ was a popular activity, and specialist hobbyists would study birds, butterflies, malacology/conchology (seashells), insects and flowers. In a post-Darwinian world, Victorians fantasied that ‘living dinosaurs’ might be found not quite as extinct as had been expected. Charles Lyell wrote in his 1830 work Principles of Geology “The huge iguanodon might reappear in the woods, and the ichthyosaur in the sea, while the pterodactyl might flit again through umbrageous groves of tree-ferns”[6], hypothesising about a return of long-extinct monsters.

![Image: Water colour by the Reverend G. E. Howman (From Martill 2013), reproduced in Mary Anning and the Flying Dragon [https://paleonerdish.wordpress.com/2016/05/20/mary-anning-and-the-flying-dragon]](https://victorianist.files.wordpress.com/2016/10/essex-serpent-4.jpg?w=470&h=330)

Image: Water colour by the Reverend G. E. Howman (From Martill 2013), reproduced in Mary Anning and the Flying Dragon

Cora, woman of science, is swayed by the idea of the serpent and wishes to find it, document it, and exhibit it in the British Museum. Will, as a man of God, doesn’t believe a word of it.

At her talk, Perry said: “This environment had dramatic tension, a post-Darwin world with the remnants of folklore. It’s like a pressure cooker to put people in – all these great ideas bucking up against each other.”

As Will says ‘This is nothing more than the Chinese whispers of a village which has lost sight of the constancy of their Creator. It’s my duty to guide them back to comfort and certainty: not give in to rumour’. ‘And what if it is neither rumour nor a call to repentance, but merely a living thing, to be examined and catalogued and explained?’(123), replies Cora.

The novel plays with the pervasive fascination with the ‘real’ origins of mythological monsters – the giant species of lizard known as the Komodo Dragon, and the giant skulls of elephants, discovered without their tell-tale trunks, interpreted as the remains of long dead cyclopeans. The griffin, in fact, has a directly paleontological history – in the Gobi Desert, fossils of the dinosaur Protoceratops was found, featuring a bird-like beak . ‘Often she thought herself childish and credulous to be in pursuit of a living fossil in (of all places!) an Essex estuary, but if Charles Lyell countenanced the idea of a species outwitting extinction, so could she. And hadn’t the Kraken been nothing but legend, until a giant squid pitched up on a Newfoundland beach, and was photographed in a tin bath by the Reverend Moses Harvey?’(144).

Interestingly, English folklore often features cryptozoology, and legends arise around mysterious and terrifying creatures which stalk specific corners of the Isles –Black Shuck, a ghostly black dog, roams the coastline of East Anglia, the Beast of Bodmin Moor, a phantom wild cat, haunts the countryside in Cornwall, and the Beast of Dean cryptid inhabits Gloucestershire’s Forest of Dean. Nessie herself is namedropped in The Essex Serpent, a possible plesiosaur set to be discovered lurking in her Scottish loch by Victorian naturalists – ‘they say a man was killed out swimming, and St Columba sent the beast away’(191).

Image: Many depict the Loch Ness Monster as a Plesiosaurus, such as in this illustration from Extinct Monsters (London: Chapman & Hall, 1896). Labelled for reuse.

The Blackwater Estuary chokes up multiple red herrings (or watery Essex Serpents), leaving the reader with no real answer as to what the creature is, or was, or could be. This is not a novel about the merits of scientific rationalism over religious zeal, or about faith trumping the analytical scepticism of the Victorian age; it is, instead, a book which encapsulates a liminal space in which these occasionally opposing, often interrelated ideologies can be communicated and explored.

Exemplifying this thematic interchange, a collision of religious ideas with secular approaches is demonstrated in a scene in which a group of Aldwick children take part in a “sacrifice” to rid their village of its rotten beast. There is no coherency to the rituals they take part in, and the children reference the ‘Hunger Moon’(84), while beseeching ‘Persephone to break the chains of Hades’(85),: ‘Long ago in other lands they’d cut out hearts to bring the sun up: surely it wasn’t too much to ask that they try out a little spell for the sake of the village?’(84). Joanna, daughter of Will, echoes her father’s religious standing: ‘conscious of the need to be both stern and benevolent, Joanna imagined her father in his pulpit, and mimicked his stance’(85). Meanwhile, her friend – coral haired, webbed fingered Naomi – ‘whose mother had been of the old religion, crossed herself fervently’(85). Gathering in a long-abandoned boat which ‘had worn down to little more than a dozen black curved posts that visitors took to calling it Leviathan’; a space literally bearing the marks of local superstition: ‘love notes and curses were cut in the wood with penknives; pennies were stacked on the posts and were never spent’(84).

The text continuously demonstrates the interchangebility of the ideas, and demonstrates how they intrude upon each other’s sphere. The text makes direct and specific connections between the multiple spheres that inherit The Essex Serpent’s world. Socialism is likened to religious faith – ‘community halls and picket lines were [Martha’s] temples, and Annie Besant and Eleanor Marx stood at the altar; she had no hymn book but the fury of folk songs’(107) – and religious faith is linked to the fervour for the natural world which accompanies Cora’s science. Will is said to have ‘felt his faith deeply, and above all out of doors, where the vaulted sky was his cathedral nave and the oak its transept pillars’(113). The Essex Serpent exists in all its forms within this discursive field – changeable, hybridised, and unknowable, it also represents the discursive field itself.

As a narrative, the transition from old world religious faith to the modern altar of Victorian science sees two seemingly opposite worlds colliding and interfering, informing each other. There is undoubtedly tension between the two worlds, but the book highlights their exchange and communality far more than their differences.

Primary Text: Perry, Sarah, The Essex Serpent, (The Serpent’s Tale, Great Britain: 2016). Page numbers are indicated following quotes.

[1] Perry, Sarah, On the trail of the Essex Serpent, http://blogs.bl.uk/living-knowledge/2016/08/on-the-trail-of-the-essex-serpent.html. Web Accessed: October 1, 2016.

[2] Fyfe, Aileen, and van Wyhe, John, Victorian Science and Religion, http://www.victorianweb.org/science/science&religion.html. Web Accessed: October 7, 2016

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Dawkins, Richard, Darwin’s Five Bridges: The Way to Natural Selection, in Bryson, Bill, Seeing Further: The Story of Science and the Royal Society, (HarperPress, London: 2011), 204.

[6] Lyell, Charles, Principles of Geology, quoted in Thomson, Keith Stewart, The Young Charles Darwin, (Yale University Press, USA: 2009), 110.

Pingback: Mythic Monsters, Living Fossils, and Liminal Spaces: The Essex Serpent – Emily Turner·

Pingback: Alföld folyóirat – A neoviktoriánus állatorvosi szörny·