Emily Turner is a first year doctoral candidate at the University of Sussex, where she is studying the medical humanities with a specific focus on locating archives of patient publications produced in mental health institutions between 1850 and 1950. You can find out more by following her at https://twitter.com/emilyjessturner, or read more of her journalism and academic writing at https://emilyjessicaturner.wordpress.com.

“An artist is nothing without a model, a muse” – Desperate Romantics

Earlier this week, I talked about the mystery of Fanny Cornforth, muse and model for Dante Gabriel Rossetti, which was solved in 2015 by her biographer Kirsty Stonell Walker. A stubborn but passionate woman, Fanny seemed to disappear from history after her life as a Pre-Raphaelite Stunner and she was last known to be in London in 1906. Kirsty found that Fanny had been sent to the West Sussex workhouse, from which she was taken to Graylingwell Hospital, the West Sussex County Asylum, where she passed away in 1909 at the age of 74.

Fanny’s huge personality and working class background meant that she was regarded as uneducated and unintelligent by Rossetti’s middle class family, and she’s often remembered as a bolshy, aggressive prostitute, depicted in stark contrast to Lizzie Siddal’s supposed frailty and comparatively passive personality.

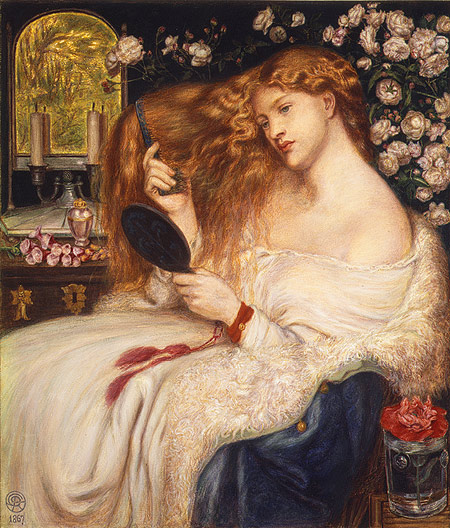

Although critical attention has been given to other Pre-Raphaelite models and muses – Lizzie, Effie Gray and Jane Morris in particular – Fanny is often sidelined, a historical factor which is reflected in Rossetti’s painting Lady Lilith. Fanny served as the original model for Lady Lilith, and her face was later painted over with that of Alexa’s (a fact Fanny was not very happy about), although her body remains in the image.

Fanny helped to represent literary characters such as Rosamund and Lady Lilith, bringing knowledge and enjoyment of these fictional worlds to new audiences – but who was she, the model and muse?

Aside from the usual difficulties in comprehending the life and inner world of a person distanced by time, it is worth considering that her representation by her peers may well have influenced her commemoration by historians, creating further distance in understanding. Fanny was often overlooked during her time as an unintelligent, unrefined woman, who was not above thieving and worked as a prostitute.

In her biography of Fanny, Stunner, Kirsty explores the legend of Rossetti’s first meeting with Fanny, who supposedly cracked nuts with her teeth and spat them at passers-by, an apocryphal story which originated with William Bell Scott. Her contemporaries were suspicious of her working-class background and attitudes, and Rossetti’s brother said ‘she had no charm of breeding, education or intellect’.

In her work Pre-Raphaelite Portraits, Andrea Rose says of Fanny: ‘She was illiterate, vulgar and […] not well liked by the majority of friends who called at Tudor House; Swinburne, Madox Brown, Hall Caine and Frederick Shields were all suspicious of her and felt that she would happily help herself to the property in the house given the opportunity’[1].

Could it be that poor contemporary opinion of Fanny has led to her being remembered as a ‘low born’ embarrassment to the Rossetti circle, or dismissed as a nut-spitting prostitute?

Rossetti was inspired by the mystic poem Donna della Finestra, and William Gaunt suggests that ‘ for him the donna was no-high born Florentine at her casement but a lively Cockney encountered perhaps in the Strand, cracking nuts with her teeth and throwing the shells about; and the face was not that of serene and gracious Philosophy but of ‘Jumbo’’[2]. Rossetti, however, ‘was perfectly happy in later life to have his friends and aquaintances meet the irrepressible Fanny Cornforth – a good-natured but coarse and very obviously working-class woman, without the benefit of Lizzie’s graces’[3].

This dismissal of Fanny’s character and personality by the historical researcher is perhaps rooted in the elitism of Rossetti’s contemporary Pre-Raphaelite circle.

Kept in abeyance by academic commemoration of the Pre-Raphaelite movement, Fanny has certainly fared poorly in her limited representation in the historical annals. In Neo-Victorian media, she fares even worse.

It could be argued that all the Pre-Raphaelites have been chronically under-represented in film and dramatic television. Stephanie Graham Pina has written a fantastic piece for the Pre-Raphaelite Sisterhood blog entitled ‘Unexpected Pre-Raphaelite Sightings’, in which she tracks the odd and unexpected places that the Pre-Raphaelites’ work emerges within the realms of filmic fiction today. Pre-Raphelite paintings have cameos in everything from The Ring 2 to Seinfield (Prosperine pops up in multiple Inspector Morse episodes) and William Morris prints provide the backdrop to Miss Marple episodes, the 1964 version of My Fair Lady, and Tarantino’s Django Unchained.

It is rare, however, that the Brotherhood themselves feature in a fictional retelling of their historical story, let alone the women who shared their world and populated their works. Although characters such as Annie Miller, Alexa Wilding and Fanny Cornforth are historical figures with real stories, skills and experiences, they often only feature in Neo-Victorian media through their representations in art.

Some of the women of the Pre-Raphaelite sphere fare slightly better than others – Effie Gray was depicted by Dakota Fanning in Richard Laxton’s 2014 biographical drama, and Lizzie Siddal, who is remembered as an artist in her own right, is commemorated with significant critical attention surrounding her creative output and has been the subject of a stage play.

However, it is a different story for Fanny. Although depicted as a character in Elizabeth Savage’s 1978 novel, Willowwood, and present ‘ as an excuse for Rossetti to combine business and pleasure’ in Ken Russell’s 1967 film Dante’s Inferno, Fanny’s most recent and perhaps most significant representation is in the BBC’s 2009 series Desperate Romantics, based on Franny Moyle’s book of the same name.

Historical fiction is often judged harshly, particularly by those who feel passionately about the era being represented. In such a case as this, the usual difficulties in accurately and creatively depicting a historical figure such as Fanny are further confused by the historical bias against the model herself. Baring this in mind, how does the representation of Fanny Cornforth in the Desperate Romantics series approach the model, given her confused place in history?

Fanny is depicted as warm-faced and deep voiced, and she is introduced, true to enduring legend, spitting nuts at passers-by. Her flirtatiousness is juxtaposed by a cut scene between her interacting with clients and Lizzie focusing stoically on her artistic work.

Rebecca Davies brings liveliness and likeability to Fanny, and her ability to emotively bring her character to life highlights Fanny’s awareness of the prejudice held against her as a member of the Victorian working-class and as a sex worker – ‘Just because I work with my below decks, doesn’t mean I don’t have a heart’.

Fanny is cautiously called a ‘free spirit’ by the Brotherhood – “She is free from the shackles of modern convention,” says Rossetti. “Or enslaved by economic circumstances,” replies a sceptical Millias. Her working-class background is fetishized by Holman Hunt, a factor she quickly capitalizes on – “lower born than Annie Miller too, sir” – and she is show to be acutely aware that her lack of formal education is correlated with her supposed dearth of intelligence. “I’ve not had clever words, that means I have no feelings at all”, she teases Rossetti – although we are shown that she diplomatically hides her emotion as she cries after the artist’s marriage to Lizzie.

The programme, dubbed ‘Entourage with easels’, is clear that it is continuing in the “inventive spirit” of the Pre-Raphaelite approach to creativity. Despite the dubious authenticity of the nut-spitting tale, and the fact that ‘recent research is strongly suggestive that she was never a prostitute’[4] (such an association being indicative of the enduring negativity towards sex workers or sexually emancipated women), the legend of Fanny as a nut-spitting, bawdy prostitute endures, a stereotype which is certainly employed in Desperate Romantics.

Fanny’s appearance in the programme is limited, and there is not enough screen time to explore her personality as there is with any of the Brotherhood. Perhaps the truth, as has been suggested, of who Fanny ‘really was’ remains lost to the past, and Desperate Romantics is merely continuing in that tradition in favour of highlighting the artists’ lives. What Desperate Romantics does well in terms of Fanny’s story, however, is highlight the reality that Rossetti’s paintings are the enduring echo of her story in the modern world.

The subject of Rossetti’s 1859 painting Bocca Baciata’s is taken from the fourteenth-century Decameron by Giovanni Boccaccio, a series of novellas about a woman who has had eight lovers before marrying her ninth.

‘Unlike the moral message in most literary works of its era, the woman is not condemned for her sexually liberated behaviour. Instead, she is hailed as the most beautiful woman in the world, a woman in full command of her sensuality and generous in its bestowal’[5].

In Desperate Romantics, Rossetti says to Fanny: “The world doesn’t need another fallen woman painting…I’m going to paint a celebration of your sensuality.” Fanny cheekily bites a mouthful from the apple he places in front of her to create Bocca Baciata.

Big, beautiful, and full of life – maybe this is the most accurate, truthful way to remember Fanny Cornforth.

Fanny is, as Kirsty says, ‘the patron saint of overlooked women’, always ‘in the background of so many stories about other people’[6].

Because of this, a fundraising drive has been launched in Chichester, led by fans of the muse and model who think that her life and contributions should be commemorated. #RememberFanny, an initiative supported by the Pre-Raphaelite Sisterhood, is hoping to raise money to commission a fitting memorial to Fanny and ‘all that this incredible woman achieved in her life’.

As she was buried in a common grave, she shares her plot with other people and therefore it is impossible to have an individual headstone for her, but the #RememberFanny team are planning to commemorate her life with a memorialising tribute.

Sarah Rance-Riley, who is championing the #RememberFanny campaign, was also the project manager of the Graylingwell Heritage Project. This was a Heritage Lottery Funded project which worked with members of the local community to put together a creative history of the West Sussex asylum where Fanny spent her last days.

She said: “The discovery of Fanny Cornforth’s last years and burial place happened during the final weeks of the GHP. Obviously, this caused lots of excitement, both for the project team and for the wider community – and the interest hasn’t diminished since. I’ve had all sorts of people ask me about Fanny and where she’s buried over the past year and after speaking with Kirsty, we thought the time was right to put a plan into action in order to properly memorialise Fanny. It really is heartbreaking to know that like others during that period, she was buried in an unmarked grave and essentially forgotten. We hope to remedy this and create a suitable space for people to pay their respects to Fanny in the coming years.”

It is hoped that Fanny’s tribute can be installed to be unveiled on April 9, 2017. As Kirsty said: ‘that is the date of Rossetti’s death and in the eyes of many of his contemporaries it should have been the day that Fanny was wiped from Pre-Raphaelite history. I think it is wonderfully and wickedly fitting that we should unveil the memorial to her on that day’[7].

Please support the #RememberFanny campaign at https://www.gofundme.com/2t976wtw, and watch this space for future updates as Fanny’s life and contributions are unveiled and celebrated, more than one hundred years after her death.

______________

[1] Rose, Andrea, Pre-Raphaelite Portraits, (Oxford Illustrated Press, Great Britain: 1981), 110.

[2] Gaunt, William, The Pre-Raphaelite Tragedy, (Cardinal, Sphere Books Ltd: 1975), 43.

[3] Ibid, 58.

[4] Hawksley, Lucinda, Lizzie Siddal: Face of the Pre-Raphaelites, (Walker & Company, New York: 2004), 150.

[5] Hawksley, Lucinda, Lizzie Siddal: Face of the Pre-Raphaelites, (Walker & Company, New York: 2004), 151.

[6]

Kennedy, Maev, From siren to asylum: the desperate last days of Fanny Cornforth, Rossetti’s muse, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2015/apr/13/discovered-lost-grave-pre-raphaelite-beauty-modelled-for-rossetti. Web Accessed Monday, April 13, 2015.

[7]

Stonell Walker, Kirsty, Remember Fanny, http://fannycornforth.blogspot.co.uk/2016/10/rememberfanny.html. Web Accessed October 20, 2016.

Pingback: Desperate Romantics: Will the Real Fanny Cornforth Please Stand Up? – Emily Turner·

Pingback: Desperate Romantics: will the real Fanny Cornforth please stand up? – #RememberFanny·