Dr Lauren Alex O’Hagan is a Research Associate in the Department of Sociological Studies at the University of Sheffield. Her research interests and publications focus largely on class conflict, literacy practices and consumer culture in late Victorian and Edwardian Britain using a multimodal ethnohistorical lens.

The rise of social media has brought attention to the phenomenon of trolling, defined by Urban Dictionary as the “deliberate act of making random unsolicited and/or controversial comments on various internet forums with the intent to provoke an emotional knee jerk reaction from unsuspecting readers to engage in a fight or argument.” But long before the days of Twitter and Facebook, the Victorians had their own way of trolling: the Vinegar Valentine.

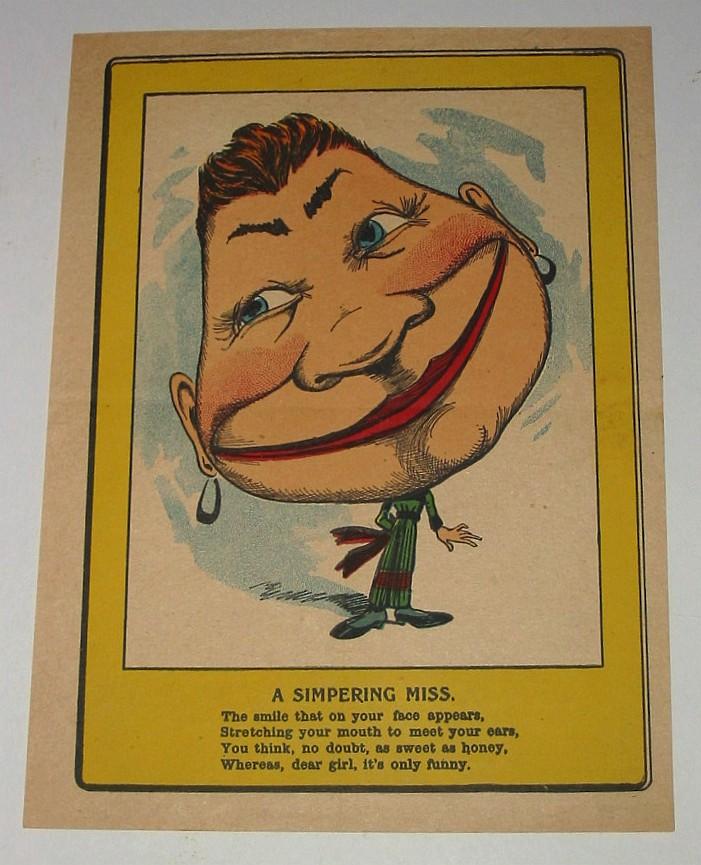

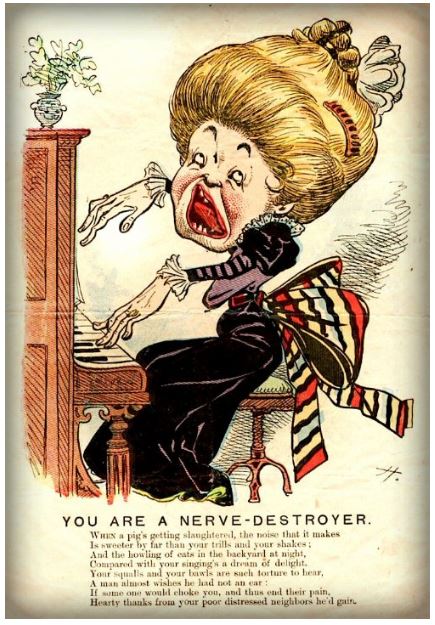

We might associate Valentine’s Day with roses, chocolates and a general feeling of love and happiness, but for the Victorians, February 14th was also a day to send anonymous rude, cruel and insulting cards to unsuspecting enemies. Vinegar valentines were cheaply made and usually printed on one side of a single sheet of paper. They typically featured a caricature with an insulting poem alongside, anything from ‘the nerve destroyer’ and ‘scandle-monger’ to the ‘slob’ or ‘bald head’. These valentines were primarily sent and received by women, fitting very much with Victorian moralism and the ideas of how a ‘proper’ woman should behave.

A Brief History of Vinegar Valentines

These cards were first produced in the USA during the 1840s, but their popularity quickly spread to Britain and was promoted by new forms of industrial print production, increasing literacy rates and the development of the postal service. Annebella Pollen (2014), an expert in material and visual culture, notes that by the 1870s, as many as 750,000 insulting valentines were being sent each year. In fact, by the late 19th century, the leading producer of vinegar valentines was none other than Raphael Tuck & Sons, “Publisher’s to their Majesties the King and Queen of England.”

The cheap cost of vinegar valentines (just halfpenny or a penny) was a key factor in their widespread use. This was particularly true in the early days when letters were paid for on delivery. So the poor targets of this hate mail would have paid themselves for the ‘pleasure’ of being insulted. The anonymity of card-sending guaranteed by the mail service also influenced their extensive uptake. Just like today, the ability to stay hidden behind an offensive message offered protection to the sender and gave them relative freedom to criticise and insult the recipient.

One bestseller, ‘A Face That Would Stop a Clock’, showed an overexaggerated portrait of an ugly woman with the poem:

In prison you ought to be doing some time,

For to wear such a face must be surely a crime

If you ‘mongst Gorillas had chanced to be born,

They would have disowned you with loathing and scorn;

For a money – no matter how homely a brute –

When placed beside you would be ranked as a “bute.”

Media Reactions

Just as now, these early forms of ‘trolling’ produced much outcry from the media. The Lichfield Mercury considered them to be “a horror that should be promptly suppressed,” while The London Daily News described them as “an abomination.” All generally agreed that vinegar valentines had ruined this romantic holiday by vulgarising humour. As the campaign for women’s suffrage gained traction towards the end of Queen Victoria’s reign, new types of cards emerged onto the market, aimed at those opposed to women’s right to vote. According to the Evening Express, these cards “were offensive as ever” with “atrocious monstrosities designed to enrage the bicycle girl” and “a score of travesties” including “mannishly-attired women” and “hen-pecked men” in skirts caring for babies and attending to household duties. One example warned “To a suffragette valentine, Your vote from me you will not get, I don’t want a preaching suffragette.”

There is a certain irony in the fact that many of these berating articles appeared alongside advertisements for vinegar valentines. One advert in the Tottenham and Edmonton Weekly Herald boldly told readers to buy a vinegar valentine to “get your own back on an enemy.” It is unsurprising that such statements led to violence on occasions. Newspapers reported frequently of fights and arguments breaking out as recipients guessed who the anonymous sender was. In one extreme example, reported in The Pall Mall Gazette (cited in Pollen, 2014), a man shot his estranged wife in the neck with a revolver after she sent him a vinegar valentine. Nonetheless, the Post Office did attempt to maintain standards by stopping openly offensive cards from being sent. The police also banned the sale of inappropriate cards in stationers and booksellers. Whether they went far enough in their clampdown is a similar debate to that being asked to social media companies and police today in the fight against online trolling.

Vinegar valentines even have their place in popular culture. In Lark Rise to Candleford (1945), the postmistress Laura Timmins receives a crudely-drawn printed caricature of a postmistress warning her that she thinks herself “so la-di-da” and that she has “a face that frightened the cows.” Lark Rise is a semi-autobiographical account of author Flora Thompson’s life. Therefore, Laura’s reaction gives us a clue to how real-life recipients would have responded to these nasty cards: “she thrust it into the fire and told nobody, but for some time all pleasure in her own appearance was spoiled and the knowledge that she had an enemy rankled.”

Given their offensive messages, it is unsurprising that so few vinegar valentines have survived the test of time. Most recipients are likely to have done what Laura did and throw them away or burn them. On social media, we have the option to block and report trolls, but, unlike vinegar valentines, their messages often remain online as a bitter reminder of just how cruel some people can be.

The Decline of Vinegar Valentines

The vinegar valentine’s popularity began to decline following the First World War. A number of reasons have been suggested for its disappearance, from commerciality and its adoption by all classes to a decline in card-giving, improved education and lack of interest in ‘low’ comedy. Annebella Pollen (2014) believes that the cards survived in new, diluted forms such as the comic postcard. A 1950s valentine’s postcard in the style of Donald McGill, for example, shows a man in a posh suit strutting down a street accompanied by the poem “a man of leisure people think, as down the street you stroll, they’d be surprised if they only knew, you were off to draw the dole.”

We often talk about the many positives that the growth of literacy, the postal service and printing had on the lives of the Victorians, but we seldom stop to think about the darker side. Together, these three inventions were responsible for the commodification of the long ritual of insult in the form of the vinegar valentine. The same could be said about the impact of the internet and social media today. According to cultural historian, Leigh Eric Schmidt, vinegar valentines “provided people with the opportunity to mock […] those who did not conform to expected gender roles, those who were seen as marginal or different.” These sobering remarks show us that, sadly, not much has changed 150 years on.

Works Cited

Evening Express, 13 February 1896, p. 4.

Lichfield Mercury, 12 February 1886, p. 5.

London Daily News, 14 February 1880, p. 3.

Pollen, A. 2014. ‘The Valentine has fallen upon evil days’: Mocking Victorian valentines and the ambivalent laughter of the carnivalesque, Early Popular Visual Culture 12(2), pp. 127-173.

Schmidt, Leigh Eric. 1993. The Fashioning of a Modern Holiday: St. Valentine’s Day, 1840-1870, Winterthur Portfolio 28(4), pp. 209-245.

Thompson, F. 1945. Lark Rise to Candleford, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Tottenham and Edmonton Weekly Herald, 10 February 1904, p. 1.

Urban Dictionary. 2020. Trolling.

https://www.urbandictionary.com/define.php?term=Trolling

Reblogged this on Victorian Persistence: Text, Image, Theory.