Gemma Outen is a PhD candidate in the Department of History, English and Creative Writing at Edge Hill University. Her research is concerned with representations and constructions of gender within Wings, the magazine of the Women’s Total Abstinence Union (WTAU). You can follow her on twitter at @gemmaouten

‘By wearing the corset my wife can walk miles; before she could not walk at all!’[1]

The controversial issues of rational dress reform and the inextricably linked ‘Woman Question’ dominated gender debates throughout the end of the nineteenth and into the twentieth centuries. However, there were organisations which explicitly stated they would not consider these. When founded as a breakaway group in 1893, the Women’s Total Abstinence Union (WTAU) sought to escape the new policy proposed by the British Women’s Temperance Association (BWTA) and rather expressly stated their desire to work only on temperance reform. This was in direct opposition to the BWTA’s desire to ‘do everything’ and to continue temperance work alongside issues including ‘the Labour Question, Woman’s Suffrage, the Opium Question, and Social Purity’.[2] When examining the periodical of the WTAU, Wings, it would be expected that this would only be concerned with temperance issues and news, considered a respectable area of social reform. However, the journal did consider many other issues, including, to be discussed here, rational dress, and cycling. Of particular note though, is the tone of this consideration. They were not considered with direct reference to gender debate and the Woman Question, but instead couched in terms of health, femininity and respectability.

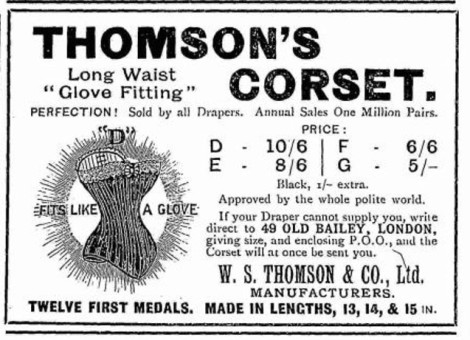

Although corsetry was not discussed editorially within Wings, advertisements were included, one with the above tagline, proclaiming the wearer’s astonishing ability to walk! However, more pertinent, the Thomson corset carried the tagline ‘approved by the whole polite world’. [3] As Margaret Beetham states, the corset ‘carried a set of meanings which concerned not beauty and nature but society and decorum’.[4] The inclusion of the Thomson advert in particular demonstrated to Wings readers that the wearing of a corset was necessary to engage in polite society and reach the required level of femininity. Women readers were instructed to participate in and embrace respectable femininity via acceptable feminine dress. Yet, as demonstrated by the quotation at the outset, some corsets were advertised as aids to health, supporting the essentially weak female body. Indeed, one knitted corset advertisement stated that the corset was ‘recommended by the medical profession’.[5] This type of advert has a distinctly authoritative, scientific tone and this medicalised selling point may have meant an increased level of success in appealing to increasingly educated women interested in scientific temperance.

However, whether sold as health aids or feminine necessities, these adverts demonstrate a tension, as corsetry required a conformity to the essential feminine whilst also reflecting an increased education, and potential interest in scientific issues. The female body, and the health of this, was clearly an issue of contestation and wider interest, reflected in the pages of Wings.

Associated with rational dress reform, the growth in cycling was linked to feminine health and demonstrated the female body as a place of potential liberation. In 1893, an advert was included in Wings which stated, ‘ladies, dispense with petticoats by wearing our knitted pantaloons. The most comfortable garment for riding, cycling, hunting, mountain climbing, touring &c.’[6] In including this advert, Wings was seemingly advocating rational dress, at the same time as including corset advertisements. However, the pantaloon advert did not reappear after 1893, nor any other advert for clothing of this sort. It seems likely that, rather than advocating rational dress, the advert was scheduled for inclusion before the acrimonious schism in the same year. After the split, the largely conservative Union seems to shy away from controversial issues such as this. Indeed, corset advertisements were only included until September 1894 and after this point ceased entirely. As the debate around corsetry and rational dress was growing, and other journals continued to carry related advertisements, this omission is curious. However, as no content was included in favour of rational dress reform, it would be reckless to assign a direct support of this by the Union. Perhaps rather, the omission is a move away from considering controversial issues more widely.

Indeed, even as cycling was increasingly visible, it was not considered editorially in Wings until 1900. In February, a Dr Crespi considered the issue asking, ‘is cycling healthy for women?’ He concluded that this was a suitable pastime, as long as the ‘distance is not too big and the cycle is light’.[7] He even prescribed a limit on this activity, stating that women should not exceed 8mph for 2.5 hours (20 miles) whilst men could ride at 9mph for 8 hours (72 miles). The Union here asserts that cycling is a suitable activity for women, but only in specific circumstances and certainly not to the same degree as men. The female body is again a place of contestation, women are now permitted some freedom but are still constrained by circumstance, namely, gender. It is further of note that this article was written by a man, here the title defers to male authority and knowledge.

By May 1901, an article by a lady temperate cyclist was included in Wings. Quite quickly, for the Union, the issue of cycling became one which was not necessarily contentious. More importantly, it was now an activity which women could write about, sharing their experiences, and thus normalising the activity. It is not included in the article just how far this lady cyclist rode however, so it is unclear whether she took the advice of Dr Crespi.

That a specifically, and explicitly, temperance-focused organisation discussed and concerned themselves with issues of rational dress and exercise is curious. They asserted outright that they wished only to deal with respectable temperance reform and the WTAU has received limited critical attention for this very reason. However, the reality is more complex. Due to the stated intention of the Union to deal only with temperance, the journal appears conservative at first glance. It begins by reinforcing respectable femininity by withdrawing rational dress items and continuing with corset advertisements for some time. Yet soon, these are also withdrawn. In withdrawing corsetry adverts and rational dress items the journal seems to be undertaking a balancing act. Rational dress is neither fully supported nor dismissed. Yet, cycling is discussed and normalised at a later point, and lady cyclists allowed to share their experiences in print, seemingly advocating this activity.

The WTAU was concerned with the wider lives of its women readers, not only in their role as temperance workers. Yet, any inclusion or exclusion of controversial issues was undertaken discreetly as the magazine sought to maintain respectability and its core readership whilst also attracting new readers and escaping unwanted attention. I believe that the WTAU, and Wings, were pushing at the limits of their own respectability. There is a complexity and tension within the pages of the journal and this balancing act demonstrates the implicit tensions in the Woman Question at the fin de siècle.

______________

[1] Every woman corset, Wings, June 1920, p. 87.

[2] ‘The Present Crisis in the British Women’s Temperance Association’, Wings, February 1893, p162

[3] Thomson’s corset, Wings, February 1894. Unnumbered page.

[4] Margaret Beetham, A Magazine of Her Own: Domesticity and Desire in the Woman’s Magazine, 1800-1914 (London: Routledge, 1996), p. 85.

[5] Knitted corset, Wings, March 1893, p. i.

[6] Knitted pantaloons, Wings, August 1893, p. ii.

[7] Wings, February 1900, p. 20.